Clinician Resources

ASTMH guidance on clinical laboratories offering testing for parasitic diseases: https://www.astmh.org/blog/march-2025/non-cdc-options-for-molecular-and-serologic-testin

Items to address before prescribing benznidazole

Have a patient with Chagas disease who needs treatment? Before prescribing benznidazole, review this helpful guidance document.

Benznidazole

Learn how to prescribe benznidazole in the US.

Atendiendo Chagas

Mundo Sano’s “Atendiendo Chagas” Network is a global network of Chagas disease healthcare providers, researchers, and other professionals. To join this international group, please follow this link: https://atendiendochagas.mundosano.org/registrarse

CDC Course: What US clinicians need to know about Chagas disease

Free online module to educate clinicians about Chagas Disease in the US.

CDC Course: Optimizing Chagas care for pregnant women and children

Free online module congenital to educate US clinicians on congenital Chagas disease practices and strategies

CDC DPDx: Trypanosoma cruzi

Information on laboratory diagnosis of T. cruzi and photos of T. cruzi and triatomine vectors

Lampit (nifurtimox) received FDA approval on August 6, 2020

Please see Lampit.com for additional information.

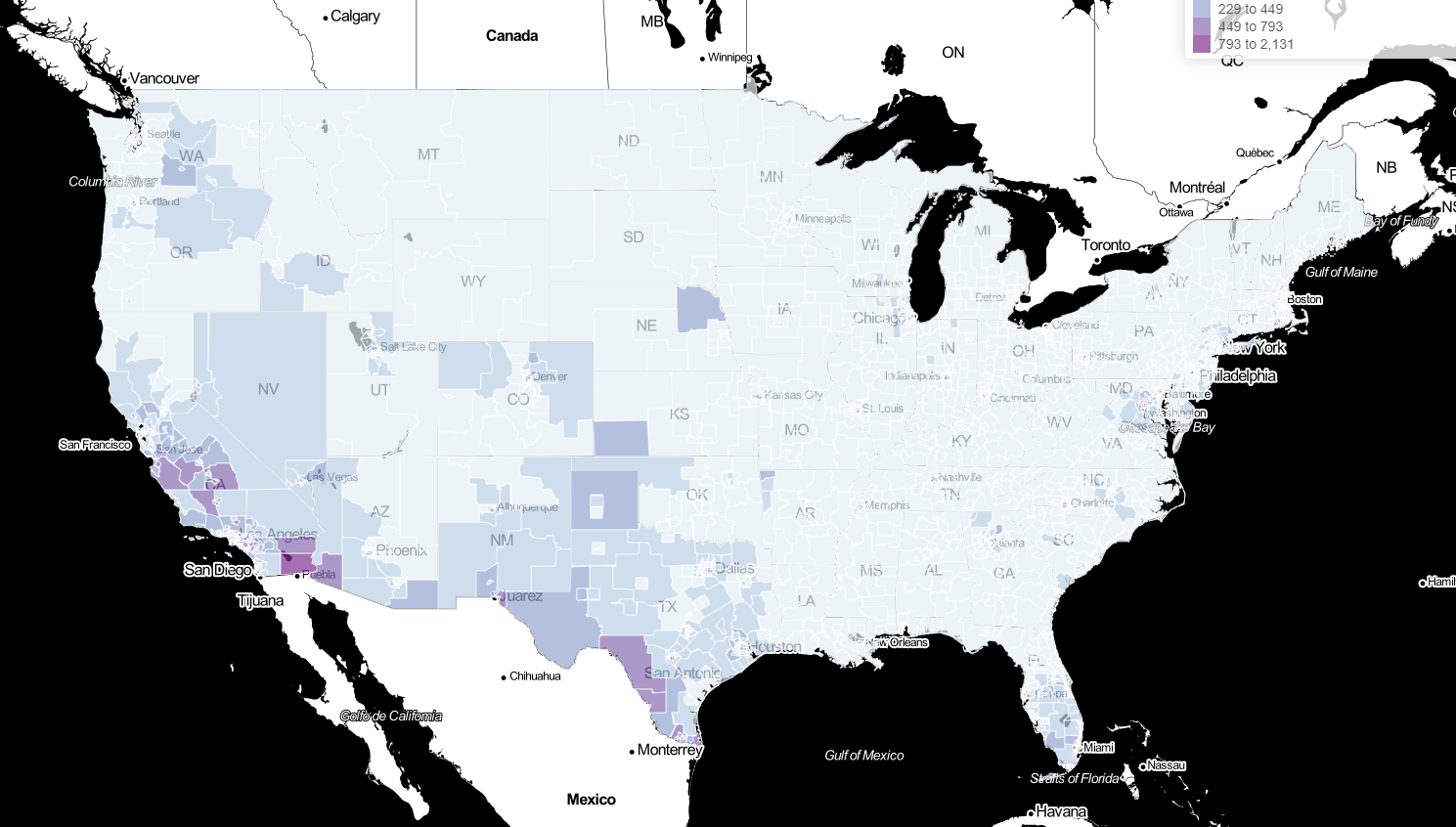

Updated Estimates and Mapping for Prevalence of Chagas Disease among Adults, United States

Map 1 - Number of T. cruzi infections in adults

Map 2 - Percent of adult population with T. cruzi infections

Map 3 - Percent of adult Latin American-born population with T. cruzi infections

Important Items to Address Before Prescribing Anti-trypanosomal Therapy in the USA

By Caryn Bern

Determine the phase and form of Chagas disease

· The acute phase consists of the 1-2 months after infection

· Patients then pass into the chronic phase which lasts the rest of the person’s life in the absence of treatment

· The vast majority of patients in the US have long-standing chronic T. cruzi infection

· Immunocompromised patients (HIV, organ transplant recipient) with chronic T. cruzi infection can have reactivation (similar to the acute phase), which may be life threatening

· How to make the diagnosis depends on the phase and form of the disease

Confirm the diagnosis [1, 2]

· Confirmed diagnosis of chronic Trypanosoma cruzi infection requires positive results by 2 distinct assays for IgG antibodies, preferably based on different antigens

· Most US commercial laboratories offer only one IgG assay

· Most IgM assays are not useful for the diagnosis of Chagas disease

· Molecular and parasitological assays are not used for the diagnosis of chronic T. cruzi infection, but are useful in the acute phase, congenital T. cruzi infection and to monitor for infection or reactivation in immunocompromised hosts [3-5]

· The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers consultation regarding patients with suspected Chagas disease and, when determined to be appropriate, offers several IgG serologic assays and PCR (Parasitic Diseases Public Inquiries: Tel.: 404-718-4745; email parasites@cdc.gov).

· Acute T. cruzi infection and infection in immunocompromised hosts may be life-threatening, and CDC may be contacted directly for rapid diagnostic advice. For suspected chronic T. cruzi infection, CDC recommends initial testing in a commercial laboratory, and contacting the appropriate state or local health department prior to contacting CDC.

Baseline clinical evaluation [2]

· Complete history and physical examination focusing on cardiac and gastrointestinal signs and symptoms

· 12-lead electrocardiogram with 30-second rhythm strip

· For patients with cardiac symptoms or ECG abnormalities: additional cardiac evaluation, including referral to cardiologist, 24-hour ambulatory ECG monitoring/holter monitor, echocardiogram and exercise testing

· For patients with signs or symptoms related to esophageal or colonic dysfunction (particularly for patients from Southern Cone countries): appropriate barium studies

· Patients should be counseled not to donate blood

· All children of infected women should be tested for T. cruzi infection

Consider the strength of evidence for benefit from antitrypanosomal therapy [2]

· Two oral medications are known to be effective against T. cruzi infection, benznidazole and nifurtimox. In the US, benznidazole is usually favored over nifurtimox due to it’s somewhat better side effect profile.

· Treatment of acute T. cruzi infection, including congenital infection in infants, is always recommended

· For chronic T. cruzi infection, the strength of evidence for efficacy varies for different age groups, with the strongest evidence base for children

· Treatment of reactivation of chronic T. cruzi infection in immunocompromised hosts can be life-saving, but data on efficacy for cure are lacking

· For adults with chronic T. cruzi infection without advanced cardiomyopathy, decisions must take into account the uncertainties about clinical benefit and frequency of adverse effects

· Treatment of women prior to pregnancy significantly decreases the risk of subsequent vertical transmission [6]. Treatment is contraindicated during pregnancy.

· In general, the younger the patient, the stronger the consensus that he or she should be treated

· Antitrypanosomal treatment has not been shown to alter the course of established cardiomyopathy [7]

Dose calculation: Benznidazole

· In the US, clinicians can obtain benznidazole through Exceltis (free for patients without insurance). To initiate this process, visit http://benznidazoletablets.com/en/Treatment.

· The standard dosing regimen is 5 to 7 mg/kg/day P.O. in two divided doses 12 hours apart for 60 days. For adults, most experts aim for 5 mg/kg/day.

· In children <12 years, the daily dose may be up to 7.5 mg/kg/day. Elimination is fastest in the youngest age groups and decreases with increasing age [8-11].

· Clinical trial data suggest that adverse events are more frequent with higher daily doses than lower ones [12, 13]. In general, we recommend an upper dosing limit of 300 mg per day, and a hard upper limit of 400 mg/day regardless of body weight.

· There is no evidence that beginning with a lower benznidazole dosage and then increasing the dosage alters the likelihood of adverse events. [14, 15]

Clinical and laboratory monitoring before treatment

· Baseline complete blood count, hepatic and renal function tests prior to initiation of treatment

· Impaired hematologic status, hepatic or renal function are contraindications to treatment

· Benznidazole should be avoided during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Women should be counseled to use effective birth control. However, benznidazole treatment was reported to be life-saving in symptomatic T. cruzi reactivation in an HIV-co-infected woman during the third trimester, and the infant was born healthy [16].

Clinical and laboratory monitoring during treatment

· Patients should be counseled to contact their treatment provider immediately if adverse events occur

· Repeat complete blood count and liver function tests every 2-3 weeks during the 60 day treatment course

· Gastrointestinal side effects may be ameliorated by timing pill administration after a meal

· Patients should avoid alcohol consumption and sun exposure during treatment

Adverse events associated with benznidazole treatment [9, 10, 15, 17-20]

· The most frequently reported adverse event is dermatitis, which occurs in 25-50% of adults and 5-25% of children

· Benznidazole-induced dermatitis is more common in females than males

· Onset of dermatitis most commonly occurs around day 9 or 10 of treatment, but may occur anytime during the course of treatment

· Arthralgia or myalgia occurs in 0 to 35% of adults

· Symptoms of peripheral neuropathy, most commonly paresthesias, occur in 25-50% of adults [9-11]

· Peripheral neuropathy tends to have onset in the second month of treatment [9-11]

· Gastrointestinal side effects, especially anorexia, occur in 15-50% of adults

· Rare but potentially serious side effects include hepatotoxicity, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia

· Adverse events are more frequent in adults than in children, and more frequent in children older than 7 years than in those 7 years or younger

· Treatment interruption due to adverse events is reported in 10-35% of adults, most commonly due to dermatitis

Management of adverse events

· Advise the patient to seek medical advice immediately if any apparent adverse effects occur

· Mild dermatitis may be managed with antihistamines and/or topical steroid cream, without interruption of treatment

· Exfoliative dermatitis, dermatitis with fever or marked angioedema, should prompt immediate suspension of treatment

· Moderate to severe dermatitis may be managed with oral steroids

· If oral steroids are prescribed, consider serological testing for Strongyloides stercoralis and/or presumptive treatment with ivermectin. Testing for latent tuberculosis infection should also be considered.

· Peripheral neuropathy, leukopenia or thrombocytopenia should prompt cessation of treatment

References

1. WHO Expert Committee. Control of Chagas Disease. Brasilia, Brazil: World Health Organization, 2002:1-109.

2. Bern C, Montgomery SP, Herwaldt BL, et al. Evaluation and treatment of Chagas disease in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA 2007; 298(18): 2171-81.

3. Messenger LA, Gilman RH, Verastegui M, et al. Towards improving early diagnosis of congenital Chagas disease in an endemic setting. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65(2): 268-75.

4. Bern C. Chagas disease in the immunosuppressed host. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2012; 25(4): 450-7.

5. Chin-Hong PV, Schwartz BS, Bern C, et al. Screening and Treatment of Chagas Disease in Organ Transplant Recipients in the United States: Recommendations from the Chagas in Transplant Working Group. American Journal of Transplantation 2011; 11(4): 672-80.

6. Fabbro DL, Danesi E, Olivera V, et al. Trypanocide treatment of women infected with Trypanosoma cruzi and its effect on preventing congenital Chagas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014; 8(11): e3312.

7. Morillo CA, Marin-Neto JA, Avezum A, et al. Randomized Trial of Benznidazole for Chronic Chagas' Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2015; 373(14): 1295-306.

8. Altcheh J, Moscatelli G, Mastrantonio G, et al. Population pharmacokinetic study of benznidazole in pediatric Chagas disease suggests efficacy despite lower plasma concentrations than in adults. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014; 8(5): e2907.

9. Miller DA, Hernandez S, Rodriguez De Armas L, et al. Tolerance of benznidazole in a United States Chagas Disease clinic. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60(8): 1237-40.

10. Pinazo MJ, Munoz J, Posada E, et al. Tolerance of benznidazole in treatment of Chagas' disease in adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54(11): 4896-9.

11. Tornheim JA, Lozano Beltran DF, Gilman RH, et al. Improved completion rates and characterization of drug reactions with an intensive Chagas disease treatment program in rural Bolivia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013; 7(9): e2407.

12. Molina I, Gomez i Prat J, Salvador F, et al. Randomized trial of posaconazole and benznidazole for chronic Chagas' disease. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(20): 1899-908.

13. Morillo C, Waskin H, Sosa-Estani S, Bangher MC, Cuneo C. Randomized comparison of monotherapy with benznidazole vs posaconazole vs their combination in asymptomatic Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2017; 69(939-947).

14. Salvador F, Sanchez-Montalva A, Martinez-Gallo M, et al. Evaluation of cytokine profile and HLA association in benznidazole related cutaneous reactions in patients with Chagas disease. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(11): 1688-94.

15. Crespillo-Andujar C, Venanzi-Rullo E, Lopez-Velez R, et al. Safety Profile of Benznidazole in the Treatment of Chronic Chagas Disease: Experience of a Referral Centre and Systematic Literature Review with Meta-Analysis. Drug Saf 2018.

16. Bisio M, Altcheh J, Lattner J, et al. Benznidazole treatment of chagasic encephalitis in pregnant woman with AIDS. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19(9): 1490-2.

17. Molina I, Salvador F, Sanchez-Montalva A, et al. Toxic Profile of Benznidazole in Patients with Chronic Chagas Disease: Risk Factors and Comparison of the Product from Two Different Manufacturers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59(10): 6125-31.

18. Altcheh J, Moscatelli G, Moroni S, Garcia-Bournissen F, Freilij H. Adverse events after the use of benznidazole in infants and children with Chagas disease. Pediatrics 2011; 127(1): e212-8.

19. Bern C. Antitrypanosomal therapy for chronic Chagas' disease. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(26): 2527-34.

20. Pinazo MJ, Guerrero L, Posada E, Rodriguez E, Soy D, Gascon J. Benznidazole-related adverse drug reactions and their relationship to serum drug concentrations in patients with chronic chagas disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57(1): 390-5.